|

|

|

Trinity-On-Main Arts Center

69 Main St., New Britain CT

www.trinityonmain.org

(860)

229-2072

Tickets:

$35, $20, $15, $5

|

|

Garde

Arts Center

325

State St. New London, CT

www.gardearts.org

(860)

444-7373

Tickets:

$50, $40, $25

|

|

MHS

Arts Center

Middletown, CT

greatermiddletownconcerts.org

For

Tickets call (860) 347-4887

|

|

Palace Theater

Waterbury, CT

www.palacetheaterct.org

(203)755-4700

Tickets: $60, $46, $35

|

|

|

|

Opening with I Pagliacci (The

Clowns), the story of the brutal Canio - opera's most famous

sad clown - and his passionate, faithless wife, Nedda, as their

traveling theater troupe brings its play to life with tragic

consequences. Featuring a hunchback who's as evil as he is ugly, one

of the great tenor arias of all time, “Vesti la giuba,” and some

rousing peasant choruses, I Pagliacci includes a play

within the play which juxtaposes the tragedy of the private lives of

Leoncavallo's clowns with the rustic humor of the Commedia.

As a comic foil, Gianni Schicchi

is as light and uproarious as I Pagliacci is dark and

gripping, and is based on an incident from Dante's Inferno.

It is the story of Gianni Schicchi, a cunning commoner, who outwits a

pack of greedy Florentine nobles and finagles a fortune for himself,

his daughter Lauretta and her beloved Rinuccio. Gianni

Schicchi is one of the funniest operas you'll ever see and is

teeming with comedic elements such as money-grubbing relatives, fake

deaths, and a frantic family fighting amongst themselves. Highlighting

the score is one of opera’s most beloved soprano arias, “O mio babbino

caro.” |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

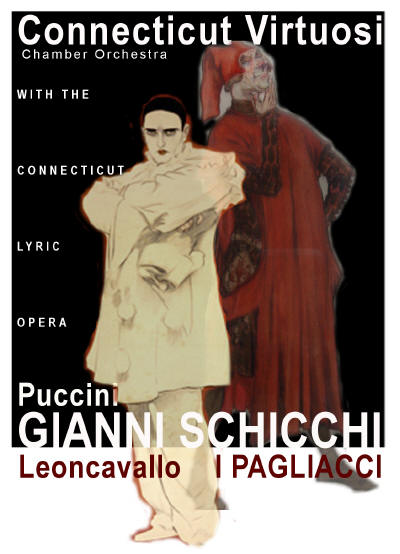

Leoncavallo - "Pagliacci" &

Puccini - "Gianni Schicchi"

Fully Staged co-production

with

the Connecticut Lyric Opera

FRIDAY, APRIL 30, 8 PM - TRINITY ON MAIN, NEW

BRITAIN

SATURDAY, MAY 8, 7:30 PM - GARDE, NEW LONDON

SATURDAY, MAY 15, 7:30 PM - MHS ARTS CENTER, MIDDLETOWN

SUNDAY, MAY 23, 7:30 PM - PALACE THEATER, WATERBURY

Conductor - Adrian Sylveen

Stage Director - Andy Ottoson

Chorus

Master - Pawel Jura

Technical Director - Peter Strand

Canio / Rinuccio - Daniel Kamalic

Gianni Schicchi - Luke Scott

Silvio - Maksim Ivanov

Nedda / Lauretta - Jurate Svedaite

|

NEW>>

Interview with Andy Ottoson, Stage Director for the production of

Pagliacci" & "Gianni Schicchi">>> NEW>>

Interview with Andy Ottoson, Stage Director for the production of

Pagliacci" & "Gianni Schicchi">>>

NEW>>

Interview with Daniel Kamalic, lead tenor for the production of

Pagliacci" & "Gianni Schicchi">>> NEW>>

Interview with Daniel Kamalic, lead tenor for the production of

Pagliacci" & "Gianni Schicchi">>>

NEW>>

Interview with Jurate Svedaite lead soprano for the production of

Pagliacci" & "Gianni Schicchi">>> NEW>>

Interview with Jurate Svedaite lead soprano for the production of

Pagliacci" & "Gianni Schicchi">>>

artic |

Andy

Ottoson has worked throughout the country as a free-lance director,

writer and designer. At Dalliance he directed his own adaptation of

Strindberg's A Dream Play as well as the world-premieres of Blind Love and

Small Talk, in addition to writing Violations. Also in New York, he

directed Jeff Lewonczyk's His First Detention with Evil Eye Productions.

He has assisted several directors, including Stafford Arima, Richard Jay

Alexander, Harold Scott, Steven Woolf, Brian Clay Luedloff, Tara

Faircloth, Edward Coffield and others. Stage Management credits include

The Dallas Opera, The Atlanta Opera, Nashville Opera, Arrow Rock Lyceum,

The Thursday Problem, Lyrico Light Opera, Union Avenue Opera and the Ozark

Actors Theater. He is a Graduate of the Webster Conservatory, where his

directing credits include Scotland Road by Jeffry Hatcher, The Lesson by

Eugene Ionesco, and Waltzing De Niro by Lynn Martin. He is a proud member

of AEA and AGMA and a member of the 2008 Lincoln Center Theater Directors'

Lab. He is currently directing the world premiere of Eliot Stockton's

Refractions at FringeNYC. Andy

Ottoson has worked throughout the country as a free-lance director,

writer and designer. At Dalliance he directed his own adaptation of

Strindberg's A Dream Play as well as the world-premieres of Blind Love and

Small Talk, in addition to writing Violations. Also in New York, he

directed Jeff Lewonczyk's His First Detention with Evil Eye Productions.

He has assisted several directors, including Stafford Arima, Richard Jay

Alexander, Harold Scott, Steven Woolf, Brian Clay Luedloff, Tara

Faircloth, Edward Coffield and others. Stage Management credits include

The Dallas Opera, The Atlanta Opera, Nashville Opera, Arrow Rock Lyceum,

The Thursday Problem, Lyrico Light Opera, Union Avenue Opera and the Ozark

Actors Theater. He is a Graduate of the Webster Conservatory, where his

directing credits include Scotland Road by Jeffry Hatcher, The Lesson by

Eugene Ionesco, and Waltzing De Niro by Lynn Martin. He is a proud member

of AEA and AGMA and a member of the 2008 Lincoln Center Theater Directors'

Lab. He is currently directing the world premiere of Eliot Stockton's

Refractions at FringeNYC.

CONNECTICUT VIRTUOSI CHAMBER ORCHESTRA

&

CONNECTICUT LYRIC OPERA PRESENTS DOUBLE BILL: LEONCAVALLO’S PAGLIACCI AND

PUCCINI’S GIANNI SCHICCHI

By John Deredita, Ph. D.

This spring Connecticut Virtuosi Chamber Orchestra &

Connecticut Lyric Opera will stage across its home state two

turn-of-the-twentieth-century short operas: Ruggiero Leoncavallo’s

Pagliacci and Giacomo Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi. Performances are Friday,

April 30, 8 p.m. (Trinity-on-Main, New Britain), Saturday, May 8, 7:30

p.m. (Garde Arts Center, New London), Saturday, May 15, 7:30 p.m.

(Middletown High School), and Sunday, May 23, 6:00 p.m. (Palace Theater,

Waterbury).

This is an unusual pairing, felicitous because both operas bring commedia

dell’arte to the opera stage. Ruggiero Leoncavallo’s Verismo drama

Pagliacci (1892) usually appears with Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana

(1890). Principals die at the end in both. Giacomo Puccini’s only comedy,

Gianni Schicchi, formed part of his three-opera bill Il Trittico (1918).

CLO assures operagoers of a balanced evening that will end on the happy

(and satirical) note provided by Puccini by presenting first Pagliacci, in

which the clown in a commedia dell’arte play kills his wife and her lover

at the finale, and then the hilarious Schicchi, which ends with the

triumph of an astute commoner who bilks a grasping aristocratic family out

of their recently deceased rich relative’s legacy and assures that his

daughter will marry the honest young man from that family whom she loves,.

Pagliacci was composed to Leoncavallo’s own libretto, loosely inspired by

a murder in Calabria adjudicated by his magistrate father but more closely

based on two nineteenth-century plays, one French and one Spanish. Perhaps

the finest play-within-a-play, self-reflexive opera ever, Pagliacci

converts the staged humor of infidelity in the commedia dell’arte into

real-life tragedy. Theatrical illusion is immediately broken in the

prologue when the hunchbacked comedian Tonio steps out of character to

address the audience directly, saying that despite depicting traditional

comic theatre, the author (Leoncavallo) will present people of flesh and

blood, a slice of life.

Once the action begins, three of the traveling players who have come to

perform in a Calabrian town behave as their characters will do in the

commedia. Tonio makes a pass at Nedda, the wife of the troupe leader Canio.

She rejects him as she will do on stage and then meets her lover from the

town, Silvio. Tonio brings Canio to discover the adulterous pair and only

another actor, Beppe, prevents Canio from attacking Nedda. When the

commedia is presented in Act II, Canio abandons his role as the cuckolded

husband Pagliaccio and demands the name of his real wife’s lover. When she

refuses to respond, he stabs her and Silvio, who steps in too late to save

Nedda. With both dead, Canio addresses both the onstage and opera audience

to tell them that “la commedia,” the play, is over, returning to the

illusion-breaking level of the prologue.

Canio’s gripping first-act aria, “Vesti la giubba” (Put on the costume),

one of the most famous pieces for tenor in all opera, is his complaint at

having to laugh and cause laughter as the character Pagliaccio when his

real-life love has been shattered. It self-reflexively looks forward to

the opera’s outcome, when Canio sings his other impassioned aria rejecting

his commedia role, “No, Pagliaccio non son” (No, I am not Pagliaccio).

Other excellent arias are Nedda’s wistful invocation of the freedom of

flying birds, “Stridono lassù” (They shriek up there) and Tonio’s one-man

prologue with its moving andante “Un nido di memorie” (A trove of

memories), alluding to the composer’s inspiration. Throughout Pagliacci,

Leoncavallo deploys motifs adroitly and creates fascinating harmonic

structures. He never surpassed in other operas this masterpiece of Verismo.

Stage director Andy Ottoson

wrote this about the CLO production: “Pagliacci is a story about the

collapse of fantasies. Nedda had a fantasy of what her life would be like

in the theater, and with Canio it has fallen apart. She does still love

Canio deeply but can’t stand her life with him—her choice between him or

Silvio is gut-wrenching and incomplete until minutes before the ending.

Likewise, I believe Tonio is an essentially sweet man who has been

embittered by years of rejection for his ugly outside—he is overjoyed to

hear Nedda’s song, to learn she shares the same yearning for more that he

does, and genuinely believes they are kindred spirits when he courts

her…which makes her rejection all the more painful and sends him off the

deep end. Canio is a wonderful man but with a temper and machismo even he

regrets. Beppe (despite his kindness) seems to be aware that Nedda is

having an affair and conceals it. Silvio has won many girls in the past

but is surprised to find himself truly in love with Nedda—all incredibly

real situations we’ve all experienced or know someone who has.

“We’re downplaying the commedia element itself in the play. The commedia

tradition adds a barrier between the show and the audience that I think is

easily overcome with a stylized but less rigid ‘clown world’ that allows

the performers to bring more of themselves to the show within a show.

“Act I takes place in a small rural town. Our costumes look authentic, the

backdrop is photo-realistic, and the lighting richly evocative of an

August dusk. However, when we move to Act II, the ‘play-within-a-play,’ we

discover that this is indeed more than just a play. Slowly, in the

intermezzo, the drop and all the masking legs fly out, stripping us down

to the bare theater walls. As reality catches up to the lovers’ fantasy,

we in the audience are painfully aware that we are sitting in a theater

with them as it happens—there is no division between actor and audience.

The only set for Act II, then, is a simple elevated platform plus audience

benches on either side. Practical footlights illuminate the onstage

action, bringing an eerie glow to what should be a delightful commedia

dell’arte piece, turning from meta-theater to a real-life brutal killing

in what feels like the blink of an eye.”

The only death in Gianni Schicchi has occurred very shortly before the

curtain goes up. The aristocratic relatives of the deceased Buoso Donati

have gathered at his bedside in his house in Florence, feigning grief over

the corpse but in fact worried that he has left his fortune to the

monastery. The will that they find confirms their fears. Young Rinuccio

suggests that they get advice from clever, middle-class Gianni Schicchi,

but the upper-class Donatis reject dealing with someone from a lower rank.

Schicchi and his daughter Lauretta arrive because Rinuccio had sent for

them during the search for the will in hopes that the family would consent

to his marrying Lauretta. The Donatis give Schicchi the cold shoulder, but

he is persuaded to stay by Lauretta’s celebrated aria “O mio babbino caro”

(Oh, my dear Daddy) pleading with her father and declaring her love for

Rinuccio. When the doctor arrives, unaware of Buoso’s death, Schicchi

impersonates Buoso, showing the doctor that the wealthy old man is still

alive; and this induces the family to agree to his plan: he will dictate a

new will. He warns them that secrecy is crucial because falsification of a

will is punishable by the loss of a hand and exile from Florence.

In the presence of notary and witnesses, Schicchi, dressed in Buoso’s

bedclothes, dictates a will in the old man’s voice. He leaves minor things

to each of the relatives but the three major items, including the house

they are in, “to my dear, affectionate, devoted friend Gianni Schicchi.”

With the notary gone, the relatives erupt in fury, seizing everything they

can carry as Schicchi tells them to get out of his house. Rinuccio and

Lauretta are united in a tender duet. Gianni Schicchi is taken from a

passage of Dante’s Inferno; and at the end of the opera Schicchi turns to

the audience asking them to judge him not guilty, begging leave from

Dante, who sent him to hell.

Gianni Schicchi’s librettist, Gioacchino Forzano, using ebullient humor

and allusions to medieval Florence, turns Dante’s story into a typical

commedia dell’arte scenario—conniving relatives worrying over a will—and

Puccini’s sparkling score conveys it with awesome vivacity. The music was

progressive for Italy in 1918, with Stravinskian rhythmic vitality,

effectual motifs, well-placed dissonances, but also lovely diatonic

passages such as “O mio babbino caro,” which provides a lyrical moment at

the turning point of the action. Rinuccio also sings a fine aria, “Firenze

è come un albero fiorito” (Florence is like a flowering tree) to convince

his relatives that Gianni Schicchi, like other parvenus in the city such

as Giotto and the Medicis, has much to contribute.

Puccini used humor in La bohème and other operas, but Schicchi shows that

he could produce a whole work of comic genius.

Andy Ottoson: “Gianni Schicchi is also unique—one of the very few truly

ensemble operas. The entire Donati family are unique characters with as

much importance to the story as the title character and the young lovers.

It’s an enormous challenge for both the singers and the staging,

especially when the family has to trash, clean up, then re-trash the

entire set in under 50 minutes!

“Schicchi, of course, borders on the brink of tragedy, with a dead body

onstage and the inevitable threat of ruin for either the lovers or the

family—but from that tragic stew Puccini pulls out a rich comedy. We are

staging it in the present day. Puccini’s major themes are incredibly

relevant today, particularly our obsession with class, our habit of

spending far more than we have, and especially the value that immigrants

bring to a culture. I always like to break down the barrier between actor

and audience, and for a piece like Gianni Schicchi there’s no better way

than to show the audience a mirror of themselves onstage.

“In terms of staging, we are trying to keep Pagliacci as simple as

possible—at core, it is a story about how fiction dominates real life, but

ultimately reality crashes through illusion. At the heart of the set is

the commedia stage itself, present from the beginning as a platform, while

“life” happens around it. When the actors at last take to it as the stage,

reality quickly follows them on. By stripping away as many of the side

elements as we can, we are truly zooming in on the stage as life.

“For Schicchi we’re taking the opposite approach, creating a world where

the old man has hoarded furniture and knick-knacks in his late years. Our

stage will be flooded with expensive-looking, mismatched furniture, much

of it stacked against the walls, clothing, papers (from receipts to the

all-important will), and Buoso’s bed (which doubles as the Pagliacci

platform commedia stage),

“We begin with the low light of dawn—the family, clad in pajamas, has

urgently gathered and is barely awake as they formulate their plan. As the

opera progresses, the sun slowly rises, the room floods with an intense

sunrise when Rinuccio flings open the outside doors in his aria; and by

the end, Schicchi’s new home is bathed in warm, thrilling light.

“Overall, this is a simple romantic comedy that remains very funny to this

day. We serve the piece best by being honest to it, building strong

charaters in a strongly defined world, then get out of the way: let the

family’s greed entertain us, and let us enjoy the ultimate victory of the

‘good guys.’”

The Pagliacci cast is Daniel Kamalic, (Canio); Jurate Svedaite (Nedda);

Chad Karl (Tonio); Maksim Ivanov (Silvio); Jason Ferrandino (Beppe). In

Gianni Schicchi are Luke Scott (title role), Daniel Kamalic (Rinuccio),

Jurate Svedaite (Lauretta), Myeongsook Park (Zita), Laurentiu Rotaru

(Simone), Deanna Swanson (Nella), Sharon Davis (La Ciesca), and others.

The orchestra is the Connecticut Virtuosi.

CLO’s conductor and music director Adrian Sylveen Mackiewicz sums up the

production as “a compilation of two verismo works, each mirroring an

emotional, and thence a musical progression. Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci

builds up to a tragic end, in which the emotional well-being of all the

characters is destroyed in a mixture of jealousy and desire. Music slowly

builds up to the moment in which the husband kills his wife and her lover.

‘La commedia’ is finished.

“In Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi the death takes place at the beginning of

the opera, and thus it begins a comic but quite realistic plot of events

in which money and power become an object of truly grotesque manipulation.

Music plays along the story, with contrapuntal and rhythmic tricks and

jokes encoded in Puccini’s genius score.”

|